This is the final entry from my most knowledgeable friend Bill Petro on the history of Christmas. Enjoy.

The Star of Bethlehem has puzzled scholars for centuries. Some have skeptically dismissed the phenomenon as a myth, a mere literary device to call attention to the importance of the Nativity. Others have argued that the star was miraculously placed there to guide the Magi and is therefore beyond all natural explanation. Most authorities, however, take a middle course which looks for some historical explanation for the Christmas star, and several interesting theories have been offered.

The Greek term for “star” in the Gospel account, is the word “aster” which can mean any luminous heavenly body, including a comet, meteor, nova, or planet (wandering star). The Chinese have more exact and more complete astronomical records than the Near East, particularly in their tabulations of comets and novae. In 1871, the astronomer John Williams published his authoritative list of comets derived from Chinese annuals. Comet No. 52 on the Williams list appeared for some seventy days in March-April of 5 B.C. near the constellation Capricorn, and would have been visible in both the Far and Near East. As each night wore on, of course, the comet would seem to have moved westward across the southern sky. The time is also very appropriate. This could indeed have been the Wise Men’s astral marker. Comet No. 53 on the Williams list is a tailless comet, which could well have been a nova, as Williams admitted. No. 53 appeared in March-April of 4 B.C. — a year after its predecessor — in the area of the constellation Aquila, which was also visible all over the East. Was this, perhaps the star that reappeared to the Magi once Herod had directed them to Bethlehem in Matthew 2:9? Comets do not display all the characteristics described in the full Nativity story. A planet or planets seems more likely.

The astronomer Johannes Kepler noted in the early 17th century that every 805 years, the planets Jupiter and Saturn come into extraordinary repeated conjunction, with Mars joining the configuration a year later. Since Kepler, astronomers have computed that for ten months in 7 B.C., Jupiter and Saturn traveled very close to each other in the night sky, and in May, September, and December of that year, they were conjoined. Mars joined the configuration in February of 6 B.C. The astrological interpretation of such a conjunction would have told the Magi much, if, as seems probable, they shared the astrological lore of the area. Jupiter and Saturn met each other in Pisces, the Fishes.

In ancient astrology, the giant planet Jupiter was styled the “King’s Planet,” for it represented the highest god and ruler of the universe: Marduk to the Babylonians; Zeus to the Greeks; Jupiter to the Romans. The ringed planet Saturn was deemed the shield or defender of Palestine, while the constellation of Pisces, which was also associated with Syria and Palestine, represented epochal events and crises. So Jupiter encountering Saturn in the sign of the Fishes would have meant that a divine and cosmic ruler was to appear in Palestine at a culmination of history.

Meanwhile, new research on the star based on recently available astronomy software and historical research on 1st century Jewish historian Josephus‘ manuscripts is being conducted and collected at www.bethlehemstar.net.

Bill Petro, your friendly neighborhood historian

www.billpetro.com

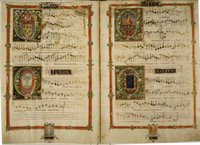

While the Christ Church choir performed it, along with the choir from St. Patrick’s Cathedral located three blocks away (pictured at right), the actual performance was done at Neal’s Music Hall on Fishamble Street half a block away from Christ Church on April 13 (pictured below.) For a while, Handel lived about a mile away, north and across the River Liffey. The music hall no longer exists, but the plaque below commemorates its location. The premiere was a benefit for prisoners in jail for debt as well as for a hospital and an infirmary. Enough money was raised to free 142 unfortunate debtors. It premiered in London a year later, but under the name “

While the Christ Church choir performed it, along with the choir from St. Patrick’s Cathedral located three blocks away (pictured at right), the actual performance was done at Neal’s Music Hall on Fishamble Street half a block away from Christ Church on April 13 (pictured below.) For a while, Handel lived about a mile away, north and across the River Liffey. The music hall no longer exists, but the plaque below commemorates its location. The premiere was a benefit for prisoners in jail for debt as well as for a hospital and an infirmary. Enough money was raised to free 142 unfortunate debtors. It premiered in London a year later, but under the name “

Recent Comments